Mediatization of witches

While media has long played a role in introducing magical practices to wider audiences—books, magazines, and TV have historically been significant in popularizing Paganism—the more recent increase in internet access further contributes to the growing number of Pagan practitioners across the globe.

Reference: Renser, B., & Tiidenberg, K. (2020). Witches on Facebook: Mediatization of Neo-Paganism. Social Media + Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120928514

Abstract

This article investigates the mediatization of neo-Paganism by analyzing how Estonian witches use Facebook groups and Messenger and how Facebook’s affordances shape the neo-Paganism practiced in those spaces. This is a small-scale exploratory study based on ethnographic interviews and observational data. To understand the mediatization of neo-Paganism, we use the communicative figurations model which suggests three layers of analysis: framing, actors, and communicative practices. For a more granular understanding of these three on social media, we rely on the framework of affordances. We found that social media neo-Paganism is (1) characterized by networked eclecticism; (2) enacted by witches who amass authority by successfully using social media affordances; and (3) consists of practices and rituals that are preferred by seekers, easily transferable to social media settings and validated by Facebook algorithms. Social media neo-Paganism thus is a negotiation between authoritative witches, seekers, and platform affordances that validate some practices over others.

Keywords: digital religion, Facebook, neo-Paganism, mediatization, communicative figurations, affordances, authority, ritual transfer online, witches

Introduction

In recent decades, neo-Paganism as a religious phenomenon has flourished across the world (Rountree, 2017). While media has long played a role in introducing magical practices to wider audiences (Hiiemäe, 2015)—books, magazines, and TV have historically been significant in popularizing Paganism (e.g., Berger & Ezzy, 2009; Possamai, 2005)—the more recent increase in internet access further contributes to the growing number of Pagan practitioners across the globe (Strmiska, 2005, p. 43). Moreover, social media has allowed neo-Pagan practitioners to enter into active dialogue with each other. This has, as we will show in this article, changed the content and structure of these practices.

This small-scale study explores the mediatization of neo-Paganism on social media. More specifically, we analyze Estonian online witches who use Facebook groups and Messenger to counsel people seeking answers from the spiritual realm (hereinafter, “seekers”). We ask how social media shapes our participants’ beliefs and practices, how its affordances structure authority and how neo-Pagan counseling practices have been altered when carried out in social media. The article contributes to social media research and digital religion research by exploring how the sociality afforded by social media as well as the features, functions, and limitations of social media platforms shape the mediatization of neo-Pagan practices, significantly transforming them in the process.

Our approach sits at the intersection of mediatization, social media, and digital religion1 studies. Research on the mediatization of religion has mostly taken on an institutional approach (e.g. Hjarvard, 2008), focusing on religious representations in media and asking how media institutions shape the understanding of religion. Meanwhile, neo-Pagan practices are non-institutional and increasingly conceptualized through Hamilton’s (2000) „pick and mix” religion model that highlights the blurring boundaries between local and global, past and present. Digital religion research examines how these kinds of traditional beliefs and practices translate to online contexts and how religion is re-imagined in new spaces (Campbell, 2017, p.16). Research on social media, in turn, explores how religious communities function in digital settings (Campbell, 2013a; Hutchings, 2013). However, there is little available on how social media shapes the neo-Pagan practices of those practitioners who use it to counsel seekers.

To understand how neo-Pagan practices are mediatized (Lundby, 2014) on social media, we rely on the model of communicative figurations (Hepp & Hasebrink, 2018) and the conceptual framework of affordances (Evans et al., 2017). The communicative figurations framework invites analyzing the mediatization of neo-Paganism through the lens of leading topics, actors in the network, and their practices. The framework of affordances allows exploring how these topics, actors, and practices have been enabled, shaped, and constrained by social media generally and Facebook specifically.

Mediatizing Neo-Paganism

Mediatization describes the long-term processes during which sociocultural change is interrelated with media change (Lundby, 2014, p. 19). The social constructivist approach to mediatization, which we subscribe to in this article, is more actor than media-centered—it takes social phenomena and their actors as a starting point of the analysis, and then observes how the phenomena are affected by the media environment (Hepp, 2014, p. 85).

Mediatization research has not specifically focused on online interactions (Campbell & Evolvi, 2019, p. 3). To fill this gap, we incorporate the concept of affordances to further address how the logics and architecture of social media platforms shape neo-Pagan practices. While there is a multitude of approaches to understanding affordances, they can broadly be defined as a “‘multifaceted relational structure’ (Faraj & Azad, 2012, p. 254) between an object/technology and the user that enables or constrains potential behavioral outcomes in a particular context” (Evans et al., 2017). Tiidenberg and Siibak (2018) suggested using the seven key concepts which Nancy Baym (2015) had proposed for comparing mediated interactions with face-to-face communication as general social media affordances. We follow this suggestion, and analyze the relational structure between Facebook and the users, specifically in terms of how much it affords:

1. Variability in interactivity;

2. Temporal malleability;

3. Manageability of the shortage of social cues;

4. Possibility to store and search content;

5. Potential for reaching a wider audience (Baym, 2015).

As an extra, we incorporate one further affordance:

6. Networked information access, which according to Halpern and Gibbs (2013) means that social media has the potential to expand and diversify (or contract and limit) users’ access to information via algorithmic and featured linkages (e.g., newsfeed updates, notifications, seeing the likes of your friends). All of the aforementioned affordances play a role in shaping neo-Paganism as practiced in Facebook groups and Messenger chats.

To analyze the process of mediatization of neo-Paganism, we use the heuristic of “communicative figurations ‘which can be described as’ (typically cross-media) patterns of interweaving through practices of communication” (Hepp & Hasebrink, 2018, p. 29). The concept permits a holistic focus on the actors and audiences, production and uses, texts and practices of a mediatized phenomenon (Lohmeier & Böhling, 2018, p. 348). Three layers of analysis are suggested: analysis of frames of relevance, analysis of constellations of actors, and analysis of communicative practices (Hepp & Hasebrink, 2018, pp. 15–58).

Frames of Relevance

According to Uwe Hasebrink and Andreas Hepp (2017, p. 366), each communicative figuration has dominant frames of relevance. These define the leading topic and guide its constituting practices. In the context of this study, neo-Paganism functions as the broad frame of relevance that binds the figuration together.

Neo-Paganism is notably a heterogeneous term, however, some common characteristics can still be identified in contemporary Pagan beliefs. As described by Maria Beatrice Bittarello (2008, pp. 221–222), these include the absence of a normative sacred text, non-hierarchical authority models, respecting the individual choice, offering heterogeneous interpretations of the divine, emphasizing the importance of practice over belief, reevaluating magic, recreating myths and rituals, and believing in the idea of a sacred Earth. Furthermore, Michael Strmiska (2005) points out that neo-Pagan thought has various manifestations that can be scattered along a continuum of the “reconstructionists” who aim to resurrect the ancient traditions of their geographical location or ethnic group—on the one end; and the “eclectics”—Pagans who mix traditions across space and time boundaries—on the other. Furthermore, neo-Pagan actors can be either communal or solitary. The former gather in communities, during festivals and events, the latter practice their beliefs alone. The surfacing of solitary practitioners has been linked to greater access to learning materials through movies, books, and the internet (Berger, 2019, p. 54).

Constellation of Actors

A constellation of actors is a network of individuals who communicate with each other within the figuration (Hasebrink & Hepp, 2017, p. 366). In the neo-Pagan sphere, these can be aspiring and self-acclaimed witches, seekers, as well as outcasts. In this article, we focus on active neo-Pagan practitioners and ask how their authority is claimed, assigned, and construed in the Facebook groups.

Much of the prior research on religious authority relies on the work of Max Weber (1978) and his proposed three forms of domination: rational–legal, traditional, and charismatic. According to Weber, the magician is a charismatic authority whose leadership relies on voluntary obedience of followers. However, he also finds that this type of authority is prone to routinization, leading to more stable forms of traditional or rational–legal authority. While Weber’s forms of domination still contribute to understanding religious leadership, several authors have described the ideal types as inefficient in the digital age. For example, Hjarvard (2016, p. 13) suggests that Weber’s model of gaining, preserving, and expressing authority does not apply in the times of modern mediated communication, as the new religious authorities are more popular, temporary, and individual in their character.

The two main schools of thought regarding the conceptualization of authority in digital religion have been well summarized by Pauline H. Cheong (2013, pp. 72–87). According to her, the first draws on the idea that the internet is a decentralized space with characteristics that erode religious authority and hence have corrosive consequences on traditionally hierarchical religious communication. Here, studies have shown that religious leaders are worried about the loss of their authority or their sole legitimacy in interpreting religious tenets (Barker, 2005; Rashi, 2013). The second approach highlights the connectedness, continuity, and possibility for negotiation on the internet, and sees it as an opportunity for religious leaders to regain trust and legitimacy, mobilizing people on religious topics and spreading religious ideas (Eisenlohr, 2017; Kluver & Cheong, 2007).

Communicative Practices

Finally, the figuration relies on communicative practices of the actors (Hasebrink & Hepp, 2017, p. 366). We can consider here all neo-Pagan communicative practices conducted by the actors in online and offline spaces. These could involve communicating ritual activities or counseling seekers, but include non-sacred activities, such as sharing and exchanging knowledge on Facebook, or taking part in the groups’ activities as well.

Social media has been regarded as a new platform for expressing and disseminating religious ideas (Campbell, 2013b), supporting and extending the believers’ offline religious lives (Johns, 2015), or allowing more open religious communication (Campbell & Vitullo, 2016). While these approaches support understanding neo-Paganism on social media, they are less helpful for analyzing the dynamics between practitioners and seekers in an online environment.

Counseling seekers over social media involves performing ritual practices at a distance or communicating advice in non-ritual form, often combining the two. In either of the cases, some adaptations need to be made to the original actions. For analyzing this, we borrow Nadja Miczek’s (2008) framework of ritual transfer online. First, Miczek (2008) proposes asking how the original structure or content of the ritual has been transformed when taken online. Second, she proposes examining which new aspects have been invented and added to the ritual. Third, she recommends analyzing which elements have been abandoned and excluded from the ritual.

Overall, this article analyzes the three aspects of the process of mediatization of neo-Pagan practices as shaped by the affordances of social media. First, we determine the frame of relevance by looking at the form and content of Estonian neo-Paganist practice on Facebook. We ask how social media affordances have contributed to or limited the choice of beliefs and practices. Second, we focus on the actors, and analyze how Facebook’s affordances are used and experienced as structuring authority among neo-Pagan practitioners. Third, to understand if and how neo-Pagan practices have been altered when carried out on social media, we look at ritual transfer (Miczek, 2008) and its shaping by Facebook.

Context and Methods of Study

Estonia is a fertile ground for researching neo-Pagan beliefs and practices. Neo-Paganism has found a substantial and dedicated audience among the general public. Not many Estonians say they believe in God, but 54% believe in “some sort of spirit or life force” (Eurobarometer, 2005, p. 9) and 59% believe in people with supernatural powers (Kantar Emor, 2017). Estonian religiosities could be largely characterized as “believing without belonging” (Ringvee, 2011, p. 45) and, similar to other post-Soviet countries, there is a wide variety of syncretistic beliefs and practices which are chosen to satisfy individual needs (Uibu, 2016, p. 16).

Media has played a significant role in introducing magical practices to Estonian people. During the Soviet period, folk healers were portrayed as national heroes (Kõiva, 2015). Today, too, witches are widely covered in mass media. Weekly Maaleht doubles its sales each January with its yearly horoscope by a famous astrologist (Lauri, 2015), the largest mainstream online news portal Delfi has devoted a section to spiritual matters, and the local adaptation of the international TV show “The Psychic Challenge” has contributed to the recent rise of esotericism (Vahter, 2018).

This interest in magical and spiritual matters is reflected in social networking sites. Facebook, which is the most popular social media platform in Estonia, is a home for a plethora of neo-Pagan, spiritual, and self-help groups and pages where witches, sages, shamans, and the like gather. Three of the largest groups are vibrant discussion boards with more than 20,000 members each (for context, the population of Estonia is 1.3 m).

The practitioners whom this article focuses on use a multitude of differing self-definitions that tend to appear in the titles and descriptions of the Facebook groups. Sometimes they denounce clear labeling altogether. However, for the readers’ convenience, we have chosen to use a common designation—“witch,” also used to define the actors in the most active Facebook group. In the Estonian context, “witch” is used to denote someone with supernatural powers, herbal medicine (wo)men, sages, healers, and the like (Kõiva, 2014). The term rarely carries negative connotations in Estonian. We use the term “seekers” to refer to people who are looking for help, advice, or predictions of their future.

This study is based on ethnographic interviews, conducted by Berit Renser with five respondents, as well as on observations they made in three Facebook groups between January and May, 2018. As neither of the researchers were previously part of the witchcraft community, Renser relied on the administrator of the largest group to act as a gatekeeper. She suggested interviewees whom she considered to be “real” witches, from both her own and other groups. These informants had overlapping roles: three of them were administrators of groups, three were approved counselors, and all of them were ordinary members in each others’ groups. Two of the informants were male and two female, however, there is no statistics to suggest that this sample accurately represents the witches’ gender ratio, but intends to show that male witches are active contributors to the observed groups where the majority of seekers are women.

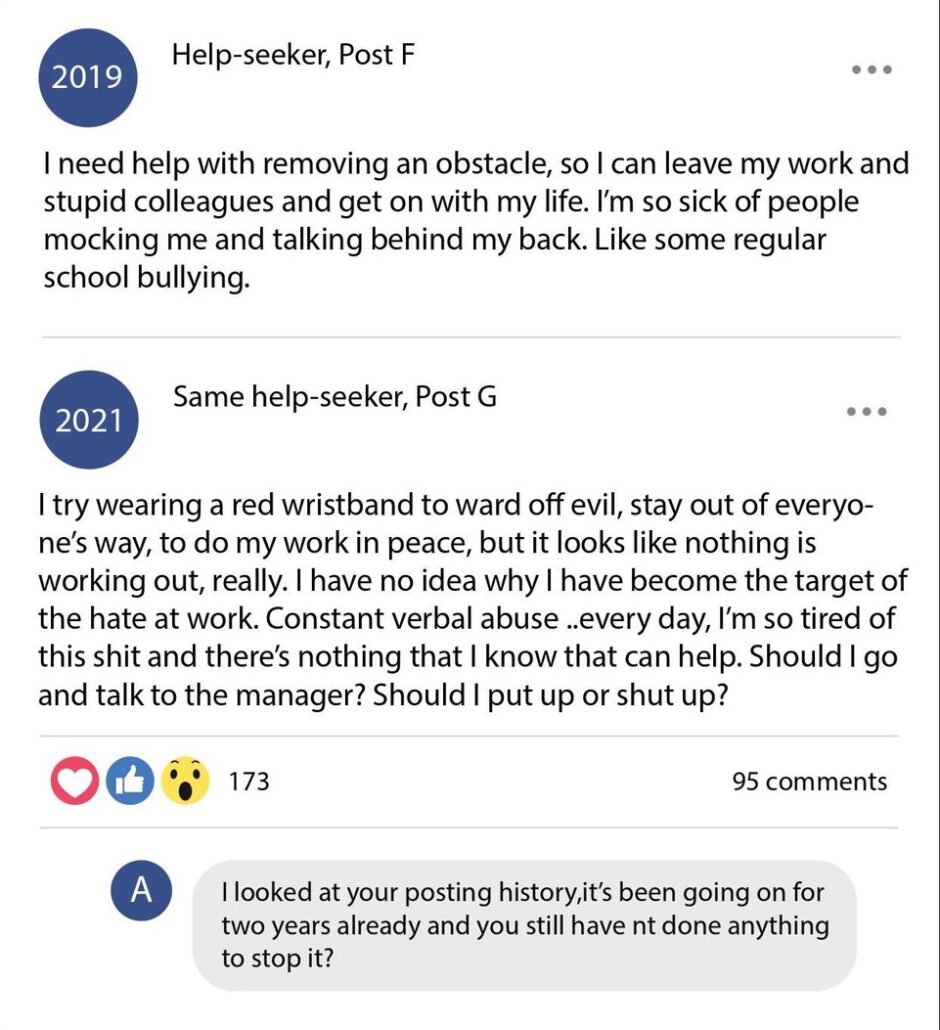

The interviews took place in the respondents’ homes and cafes and were conducted in Estonian (both authors are native speakers). During the interviews, the respondents were asked to demonstrate their ritual practices in face-to-face settings and then asked about how they transfer those rituals to Facebook. Their practices varied considerably and included the following: fortune-telling with runes, talking to the dead with the ouija board, spells, herbal medicine, Tarot and Lenormand cards, pendulum, palmistry, astrology, energy loading and channeling, and shamanic journeys. In addition, Renser followed the respondents’ Facebook activities: their pages and posts, to get a broader understanding of their social media use. The screenshots seen in the article are rough re-enactments of original posts, which Renser created to de-identify the users following the logic of ethical fabrication (cf. Markham, 2012; Tiidenberg, 2017). We changed all names of the groups and the informants to protect their anonymity, and Renser has informed consent from the informants.

Discussion of Results

Based on the threefold focus suggested by the model of communicative figurations, we analyze Estonian witches’ practices for the general frame of relevance, observe how authority is constructed in the constellation of actors, and finally, discuss how their neo-Pagan practices have transformed when taken to Facebook. In all of this, we pay attention to how Facebook affordances shape and constrain the process of mediatization.

Frame of Relevance: Eclectic Neo-Paganism

Access to information has always been crucial to learning about neo-Pagan practices, but has historically been restricted by the availability of media, geographical constraints, and literacy (Hiiemäe, 2015). The era of “deep mediatization” (Hepp & Hasebrink, 2018) offers an assortment of new and traditional media types. The studied witches find most of their information about new or revived practices through different websites and platforms, such as blogs and forums, Wikipedia, YouTube, online courses, and the internet in general. This allows the practitioners to gather, interpret, combine, and share information from different sources, and to create a highly personal blend of eclectic neo-Paganism. Therefore, we suggest that the frame of relevance of this communicative figuration is eclectic neo-Paganism. However, as we shortly demonstrate, unlike the eclecticism observed in previous studies of neo-Paganism, in the Facebook groups we studied, it is profoundly negotiated and networked.

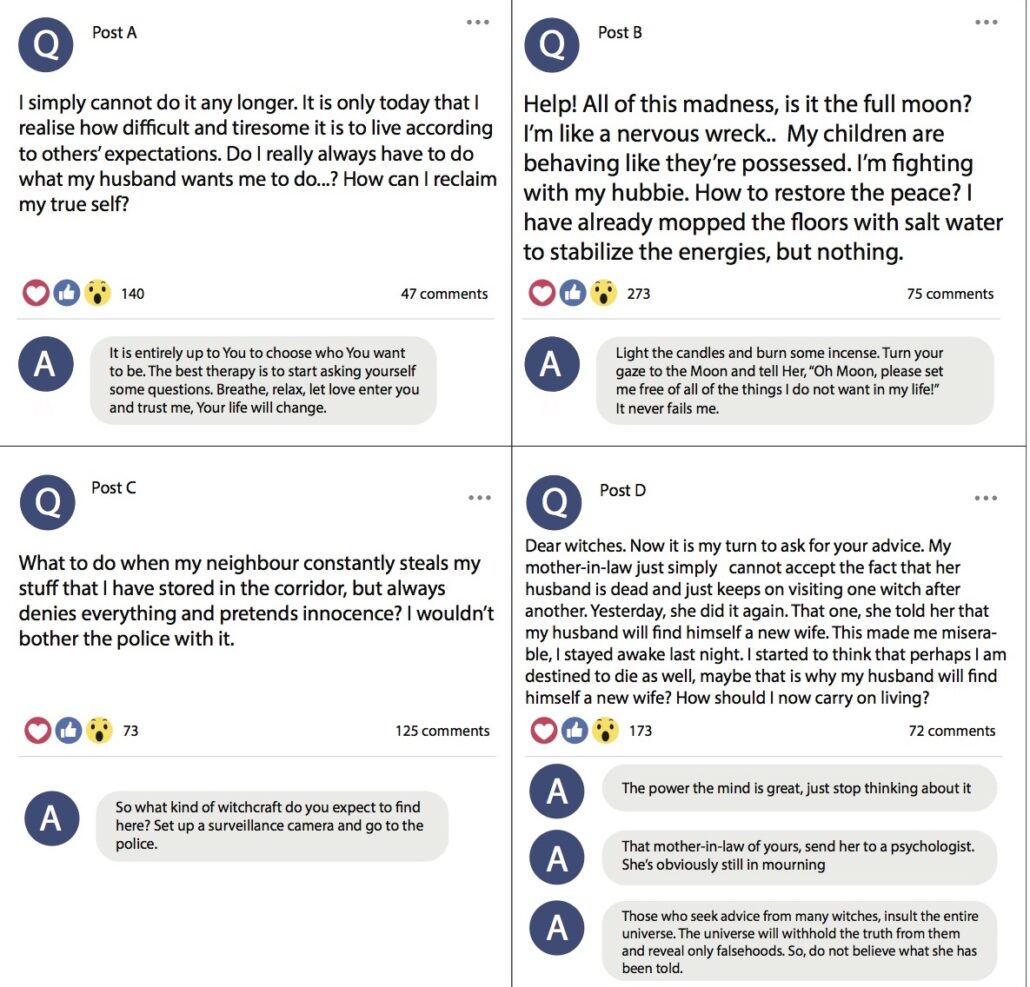

The eclecticism can be observed in both the individual choices made by the witches and the broad variety of practices accepted within the Facebook groups. These range from New Age to indigenous folk beliefs, with some references to monotheist religions, Eastern religious traditions, all infused with self-help tips (cf. Figure 1).

Figure 1. The witches advertise themselves and their specialty services on a Facebook group’s wall (ethical fabrication of a typical Facebook post).

This eclecticism is supported by several of the aforementioned social media affordances—most notably interactivity, storage, and networked information access. The seekers can and do interact with the content shared by the witches via likes, comments, and shares. While these are packaged into immediately visible popularity metrics on the Facebook interface, and thus offer mostly quantitative feedback, some group members also reach out directly and make requests or suggestions in private chats. Both types of feedback help witches determine seekers’ interests and the best ways to meet their needs, and thus shape the particular form of eclecticism that frames neo-Paganism in this space. The fact that older posts and messages remain available for searching and revisiting increases the witches’ awareness of resurgent topics, adding a dimension of time or cyclicality to how witches perceive audience feedback and how they select the elements to be included in or discarded from their eclectic mix of neo-Paganism. Finally, Facebook’s newsfeed and recommendation algorithms—relying on data generated from all of the interactions described above—(de)prioritize specific topics and thereby also shape the witches’ repertoires. Thus, which practices are validated over the others, and how the eclecticism of mediatized neo-Paganism shapes up, is, as we noted above, profoundly negotiated and networked.

Tanel Wolf was well aware of the performance of his various posts and could easily point out the winter solstice rituals as his most popular topic—something that he now posted each year. One of our informants, Little Witch, said she started off with giving advice on herbal medicine, but the high demand for fortune-telling, especially with runes, made her readjust. The popularity of angel card readings across many groups and networks made the witches suppress their own dislike for them and comply with members’ requests. “If you want those angels that much,—well, here you go!” commented Little Witch. Even more so, high demand for love-related guidance, which Little Witch herself was not interested in, encouraged her to invite witches who specialized in these issues to her Facebook group, thus shaping the conversations in and the overall tone of the group as such.

Witches’ individual foreign language skills also shape the eclectic choices made from the potpourri of global practices. For example, Little Witch feels more comfortable reading Russian. While the roots of her practices are Estonian, she gathers information from the Russian-speaking internet, and is consequently influenced by Siberian witchcraft. Another informant—Odin speaks Finnish, and is interested in Scandinavian mythology. Leena works with three languages, mixing information disseminated in Estonian, English, and Russian and adding her own experiences, as described below:

Lenormand Leena: I’m telling you this growth has happened because of the internet . . . That’s how you do it, translate from English, Russian and add your own experiences . . . I have bought courses from online and other places, in English. I hang out on YouTube all the time, hours and hours. It is frenetic, like going to school.

While the geographical boundaries are increasingly easy to overcome, some of the informants are concerned with keeping their Estonian roots and traditions. As a result, they make sure to remix local heritage with globally trendy practices, as described by Tanel Wolf:

Tanel Wolf: I would describe myself as a philosophical Pagan chaos magician who holds satanic views and practices shamanism and voodoo . . . I try to mix things, to get people interested in our own mythologies, but I do it through the already attractive voodoo.

Therefore, while the internet as such allows practitioners to formulate and promote an individual set of techniques based on demand and popularity they can gauge because of social media’s affordances, they are still limited by their own skills. Those skill-related limitations can, in turn, be amplified by social media’s affordances. To simplify, when recommendation algorithms hone in on witches’ interests in a particular practice (e.g., runes) from a particular geographic region (e.g., Siberia) and in a particular language (e.g., Russian), they afford very little networked information access, shrinking and limiting the information the witches have access to by offering more and more of the same.

Constellation of Actors: Negotiating Authority Online

For the purposes of this article, the constellation of actors within the communicative figuration of neo-Paganism is the interrelated network of neo-Pagan counselors in Facebook groups. While the social media affordances discussed in the previous section shape the practitioners’ religious eclecticism, they also shape how the witches experience and make sense of their authority and do so in contradictory ways. On one hand, our informants highlight that the plethora of voices and interpretations offered in online groups and private consultations can be cacophonous and conflicting, causing anxiety in their clients:

Little Witch: It’s becoming a catastrophe . . . One doesn’t know what to believe. Look at our posts. They are scared of everything! Karma, a feather, someone whispering, a mouse scuffling inside the wall . . . They panic, they write to me: what’s gonna happen?! Will I die today?! Isn’t it so? . . . A few years ago it wasn’t like this. I used to lurk in other witch-groups back then and it wasn’t as bad yet.

This perception echoes previous findings regarding religious leaders who see the internet as a threat to their authority and as leading to the weakening of religious messages (Barker, 2005; Hjarvard, 2013). On the other hand, the witches also perceive social media and specifically Facebook groups to have affordances that mitigate these concerns. The possibility to manage and control (to an extent) the interactivity, the social cues, and the size of an audience for particular people or posts, allows gathering solitary practitioners into loose but hierarchical communities wherein some users amass more authority than others. This is accomplished using the platform’s features both as intended and creatively.

The features that are intended to create hierarchical associations are creating groups, becoming an administrator and assigning moderators. These features allow group administrators to sit at the top of the membership hierarchy. Furthermore, being an administrator of a community is not only seen as an administrative function, it also legitimizes the administrator’s spiritual leadership:

Marit: I, myself, believe that the admins have greater rights because they have greater knowledge. They are like heads of a large community who keep order and lead us all.

Using groups’ privacy settings, accepting and declining new members and their posts, deciding who can join and contribute to the conversation are all used to create hierarchical association. While group membership can be gained relatively easily and requires answering simple questions (e.g., “Why do you want to join this group?,” “What are your expectations?”), getting banned from the group or being deleted from the list of approved readers is also commonplace. The witches explain this by alluding to the administrators’ responsibility to protect users from charlatans, whom they describe as self-promoters with no real skills, who charge exorbitant fees for their services, give readings that are too negative, take (sexual) advantage of their clients, sell harmful medicine, and so on. Therefore, the features and affordances that are seen as allowing control are positively valued by the informants:

Lenormand Leena: They have somehow nailed this, how they shape this group. This, how they weed out the people they do not want . . . This is the right system. They keep an eye on people, they have feedback on me, too . . . They have organized this well, weeding out charlatans and weirdos.

The administrators also use creative ways to control and create further layers of hierarchy beyond what Facebook’s features and settings allow. In Facebook pinned posts, in the group’s description, or in the group’s documents, a list of approved counselors is articulated, all listed with their expertise in neo-Pagan topics and tools (i.e., counseling on love and money with cards, communicating with the dead by ouija board). The methods of witch vetting vary across groups: while Group A uses mystery shopping to control the quality of service of potential counselors, Group C asks for a letter of recommendation and a certain amount of experience with card readings, and Group B collects the names of all aspiring witches and sages in a single post and invites everyone to provide feedback on their competence. Finally, some people receive personal invites by the administrators after having been active, visible, and seemingly reliable on the group’s walls.

Facebook released its group rules feature in 2018, after the fieldwork period. In the neo-Pagan groups we observed, the administrators, creatively using the empty spaces of document files, pinned group posts or group’s description fields, and set rules covering a variety of topics. Typically, declaring the ultimate authority of administrators in decision-making, providing a long list of preferred, undesirable, and banned beliefs and practices (e.g., runes, dreams, various New Age practices), or establishing prohibitions and restrictions (e.g., adult membership and access only, no ads, no photos of children or other third parties, no fishing for clients by outsiders, no radical medical advice, etc.) were listed. Group posts were monitored for their accordance with the stated rules, but ultimately depended on the administrator’s perceptions. For instance, the comment sections of public posts were sometimes closed if the topic was deemed too sensitive, and the administrators approached the seeker via chat. While they could not monitor other witches’ Messenger chats, they issued public warnings about potentially malicious users and invited users to make complaints about misconduct (this is also evident in the post in Figure 1).

While a lot of existing research has shown that social media can be an egalitarian space where the previously vertical structure of authority has become horizontal (Barker, 2005), the witch-administrators have used the affordances of social media to claim authority in spiritual matters. In addition, controlling content allows witches to define their views on witchcraft and build the groups as authoritative spaces on these matters. In Weberian terms the charismatic authority of the witches is routinized, with the help of social media affordances, through creating user hierarchies and group rules, resulting in more stable forms of authority.

Communicative Practices: Counseling Online

All six of Facebook’s affordances mentioned above shape how the neo-Pagan ritual practices performed during counseling transfer online (Miczek, 2008). The varying interactivity and the malleable temporal structure allows practitioners to communicate with their clients in multiple ways. Typically, communication happens on group walls (posts, comments) or private chats. The witches interpret the wall posts as having a higher potential to reach a wider audience and thus use them as a visibility tool that helps showcase the group as a space for magical issues, to attract more visitors, increase engagement, and build a vibrant community. In addition, posting on group walls allows the witches to grow their personal client base who can later be engaged in “more serious” private chats. Yet, commenting on posts made on the public walls by other users is the least favored activity of the informants, mainly because they are already busy with private chats and administrative duties. This leaves the comments section mainly for ordinary users. However, the informants do interrupt if they consider the content in the comments section harmful, confusing, or misleading, and may contribute with their own expert advice for further clarifications on the topic. This grants the witches access to spiritually inclined people and allows them to have a say in discussions not directly involving them. Arguably, social media thus affords greater closeness between witches and the community, and fluidly integrates their expert opinions into seekers’ lives more broadly than individual counseling would allow.

A more popular activity among the informants is curating wall posts. Some of these posts are informative in nature. The witches share spells, herbal medicine tips, general observations of the spiritual world, or daily good wishes for group members, content familiar from witchcraft coverage in traditional media. Other posts serve the purpose of entertainment. Witchcraft-related humor in the form of memes qualifies as what Miczek (2008) called the invented aspect of ritual practices. Lenormand Leena interprets it as “making fun of yourself for a good laugh,” which is not meant to trivialize magical practices, but to increase engagement and build community. An example would be a humorous visual post, where a young, nude woman is depicted sitting on a rock, with next to her a black cat and a broomstick. On the bottom of the image a text in Russian says: “I am an angel, I promise! It’s just that broomstick is so much faster . . . .” A different one offered a magic spell for Friday night that involved tequila with lemon and salt.

A notable invented format is mass-counseling through wall posts. These posts typically set the rules of partaking (e.g., time restriction and preferred topics), add a photo of the instrument used (e.g., cards, runes, or pendulum) (Figure 2), or use live video. Group members are then offered an opportunity to ask for guidance in the comments, and the witch who posted it will use the advertised tools to offer guidance for the promised duration of time. Facebook’s features of infinite scroll and automatic shortening of posts encourage fast-paced interactions around easily digestible, succinct, catchy, and visually attractive content. This has proven to be immensely popular, engaging hundreds, if not thousands, of followers. The affordances of interactivity, malleable temporal structure, potential for a larger audience, and networked information access significantly revise the communication between the witch and the seeker. It allows all members to take part in the process as the Q&A unfolds. These public interactions create engagement and increase the sense of community that solitary practitioners and their clients would otherwise not have. However, it also creates social pressure among practitioners to maintain one’s visibility and to perform these rather demanding mass-counseling sessions.

Figure 2. Tarot reading on public walls, initiated by the informant Marit, received 330 questions (ethical fabrication of a Facebook post).

The fast-paced interaction needed for mass counseling informs the witches’ choice of ritual method and tools. Repertoires are transformed so they fit the platform’s limitations. Traditional face-to-face tools and practices involve herbal mixtures, spell-casting, energetic cleansing of physical places, playing music, and so on. Taking magical practices to the walls of Facebook groups reduces this diversity notably. Time-consuming activities, such as reading the ouija board or going on a shamanic journey, are excluded (Miczek, 2008) entirely from mass-counseling. Instead, practices like card or rune reading are preferred for their easy adaptability to the social media setting. A pendulum giving simple “yes” and “no” answers also suits mediated servicing of the crowds.

Transferring ritual to social media does not only reduce the variety of tools applied, it also transforms (Miczek, 2008) the way those tools are used. Instead of reading a whole Tarot deck, only one card is drawn; instead of laying out the entire set of runes, one is picked. While these changes may be frowned upon by some practitioners who consider them too shallow to be taken seriously, the witches we studied claim to make no compromises content-wise. They argue that seemingly trivial activities, such as sharing humorous memes or mass-counseling, contribute to, carry on, and expand the understanding of witchcraft in new ways and should therefore not be regarded as mere entertainment.

However, the witches also counsel seekers in Facebook Messenger chat, which they think more closely resembles face-to-face counseling. The chats often expand into involved conversations with the seeker, much like in an offline situation, although text-based and often slower and longer lasting. The witches said they have to invest extra time in typing the answers they receive from the cards, runes, or spirits, introducing and inventing (Miczek, 2008) a written practice into the ritual. The affordance of malleable temporality permits the counselors to handle several seekers at a time, but may also extend the duration of single sessions, sometimes to days and weeks. Those witches who have a day job can now integrate witchcraft into their lives with more ease, possibly expanding the number of aspiring witches.

The affordance of storage allows seekers as well as counselors to return to prior readings. The witches see this as a great opportunity to pick up the conversations from where they had left off and introduce a more significant continuity to interpersonal counseling relationships. The witches also presume the storage to be valuable for the seekers, as it enables them to reinterpret their earlier readings from time to time.

Communication on Facebook lacks physical proximity that normally carries a plenitude of social cues—important conveyors of information about the context and people involved. The witches take advantage of Facebook’s features to invent some missing cues, while others are transformed or excluded (Miczek, 2008) from the communicative practices altogether. While the magical tools, decorations, and symbols in the informants’ homes help present it as a spiritual space, Facebook is not designed to be a spiritual space per se. The cues for making the space magical need to be transformed through the use of multimodal communication. Photos and memes that convey the neo-Pagan thought, or textual references infused with spiritual jargon, serve these purposes. However, the witches choose to exclude (Miczek, 2008) some cues that could be incorporated, most notably the voice. Facebook allows sending voice clips or YouTube links, live videos, and video chats, but the interviewed witches did not take advantage of these features. Practices considered typical in face-to-face settings, such as casting spells or playing drums, were considered too inconvenient to be transmitted over the internet. This indicates that the witches enjoy or at least have fully accepted and gotten used to the differently paced rituals consisting of often shortened or simplified magic tool use.

Among those cues that cannot be substituted and are therefore excluded (Miczek, 2008) are the physical bodies and the touch of the healer. This amounts to a significant transformation of the repertoire of practices. Estonian witches have historically served as folk healers working with spells, herbal mixtures (Kõiva, 2014), and laying of hands. Concurrently, the witches we studied in these Facebook groups have largely excluded medical problems from their repertoire, to the point that giving medical advice is altogether forbidden in some groups. Some of the witches listed in the groups do give medical consultations, but mostly when met in person. Others, instead, have refocused on psychological and lifestyle issues, such as finding love and balance in life, and solving financial and other everyday problems.

The shortage of social cues and the ability to effectively manage them offers the witches and the seekers some degree of anonymity. While pseudonym use and profile privacy settings vary among seekers, the informants interpret mediated communication on Facebook as more anonymous than face-to-face interaction and this, in turn, as advantageous for both sides. Our informants argue that the perceived anonymity in private chats contributes to the seekers’ willingness to open up, transforming (Miczek, 2008) the counseling process, so it becomes more honest and intimate than it would be in a face-to-face situation:

Tanel Wolf: Let’s say, for example during counseling, there’s anonymity online, it makes people more open. When she chats online or in real life, then in real life she’s more reserved than in her text . . . Plus over the internet, we can have contact across hundreds of kilometers.

While some witches perform under their full given names and depict themselves in their profile images, others use the shield of pseudonyms that enables them to work without having to disclose their real identity and, instead, invent (Miczek, 2008) an online persona. The latter enjoy Facebook as the sole place to perform their practices in and exclude (Miczek, 2008) offline consultations altogether. This choice is made for a variety of reasons, including the possibility to communicate over long distances, afford more flexible schedules, and mitigate shyness or anxiety of meeting people face-to-face. Practitioners state the need to protect their privacy as the main argument against accepting visitors in their home. Nosy neighbors and a queue of cars in front of the house are mentioned as common unwanted negative side effects endured by those renowned witches who do. Using the affordance of social cue management allows the witches to profit from their skills while cordoning off other aspects of their lives.

Conclusion

We have analyzed the mediatization of neo-Paganism on Facebook using the model of communicative figurations (Hepp & Hasebrink, 2018) and affordances (Evans et al., 2017). More specifically, we analyzed the frame of relevance, the constellation of actors, and the communicative practices involved in our research participants’ mediatized neo-Pagan practices. In addition, we focused on how Facebook’s affordances of interactivity, malleable temporal structure, manageability of social cues, storability, the potential of a wider audience, and networked information access transform neo-Pagan practices as they become mediatized.

Similarly to what has been argued in the previous literature (Berger, 2019), the witches we studied use the internet to find, learn, and develop an eclectic and personalized set of beliefs and techniques. Thus, the frame of relevance of the communicative figuration at hand is negotiated and networked eclectic neo-Paganism. The eclecticism of our participants is constrained by their individual preferences and foreign language skills as well as the witches’ ideological concerns with keeping Estonian traditions alive. However, besides the individual preferences, our participants’ neo-Pagan eclecticism is also shaped by the interactivity, storage, and networked information access affordances of Facebook, primarily where they shape and constrain specific forms of individual, automated, and algorithmic feedback. Thus, it is not only the witches but also the seekers and Facebook as such who shape neo-Pagan eclecticism. The group members’ preferences are inserted into the negotiation of the frame via direct requests on Messenger, posting and commenting on the group walls, or by liking and sharing content. The neo-Pagan eclecticism of the witches we studied is thus shaped by both—the interactive human, and the automated metrics-based feedback that Facebook affords. This feedback is then amplified by Facebook’s algorithmic (de)prioritization of certain content via features like notifications, recommendations, or newsfeed updates that make some topics trend over others.

Our participant’s authority negotiation practices on Facebook align with both—the earlier work that argued that the cacophony of voices online is experienced as detrimental to the perceived expertise of the practitioners (Barker, 2005), and the work that has found that it may also help legitimize religious authority (Eisenlohr, 2017; Kluver & Cheong, 2007). The lens of affordances allowed us to detail the concurrent and entangled nature of these two seemingly contradictory processes. We found that while social media affords challenging any authority, it also triggers witches’ awareness of authority and leads to conscious authority-making practices. Facebook groups (via both intended and off-label use of features and functions) allow practitioners to exert loose control over the content and membership of the groups, accomplished by listing approved beliefs, setting rules for seekers and witches, keeping an eye on ongoing conversations and trends, and recruiting and promoting practitioners, while excluding those that are not deemed as appropriate. These practices create hierarchies, contribute to the routinization of authority in Weberian terms (1978), and put witches in the position to define and reinterpret neo-Paganism.

Facebook’s affordances also shape how elements of the neo-Pagan rituals themselves are transformed, excluded, or invented (Miczek, 2008). The temporal flexibility of Facebook permits witches to service several people at the same time—both by keeping multiple one-on-one sessions via Messenger and by performing newly invented mass rituals on Facebook walls—enabling the expansion of their client base. Some traditionally time-consuming practices (e.g., Tarot readings and runes) are truncated or simplified. Together, these transformations of temporality introduce unprecedented instant gratification and 24/7 advice and support into the neo-Pagan practices and rituals. The limited social cues of social media interaction have led to further major alterations in neo-Pagan practices. The exclusion of sound, scent, or touch notably transforms the traditional counseling process. As a result, physical healing is often replaced by psychological and lifestyle guidance. The affordance of social cue management expands and diversifies the ranks of both seekers and witches. Seekers who did not reach out for face-to-face counseling, do so now. Others are more likely to open up during the counseling session. Witches who chose not to see clients face-to-face because of practical reasons and privacy concerns can now practice without hassle.

This is a very small study and our ambition is not to generalize to a population of all neo-Pagan practitioners on social media or on Facebook. However, triangulating interview data with observational data and analysis of affordances, the expert status of the informants both in terms of the subject matter and their central roles as administrators and leaders of the groups suggest that it might be useful to consider the dynamics we observed when designing future studies of digital religion, neo-Paganism, belief-based communication, or counsel-seeking on social media. We think a focus on authority, dialogue, and ritual transfer could serve as a starting point to ask further questions about how different types of groups deal with content moderation and even misinformation.

The mediatization of neo-Paganism on Facebook is a negotiation between witches, seekers, and the technological affordances of the platform. Some witches, by virtue of effort and luck, but also by successfully taking advantage of Facebook’s affordances, gain authority to define what neo-Paganism is and how it should be practiced. What these witches put forward as neo-Paganism is not only shaped by their personal preferences, but also by constant input from seekers and Facebook’s algorithms, as well as by how well particular rituals translate to social media. Mediatized neo-Paganism, as manifest in the studied Facebook groups, is thus significantly shaped by social media and is in the process of constant negotiation—not static, but dynamic, and in flux.

Acknowledgements

We are deeply grateful to the informants for sharing their lives and experiences.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author (s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author (s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Berit Renser https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3600-8691

Notes

1.Interpreting religion only as “embodied in a social institution” is being increasingly challenged (Hanegraaff, 1999, p. 147). This article focuses on religiosities in a broader sense that involves both institutional and non-institutional beliefs and practices.

References

Barker, E. (2005). Crossing the boundary: New challenges to religious authority and control as a consequence of access to the Internet book section. In Hojsgaard, M. T., Warburg, M. (Eds.), Religion and cyberspace (pp. 67–85). Routledge.

Google ScholarOpenURL Tallinna Ulikool

Baym, N. (2015). Personal connections in the digital age: Consumption markets & culture. Polity.

Google ScholarOpenURL Tallinna Ulikool

Berger, H. A. (2019). Solitary pagans : Contemporary witches, wiccans, and others who practice alone. University of South Carolina Press.

Google Scholar | CrossrefOpenURL Tallinna Ulikool

Berger, H. A., Ezzy, D. (2009). Mass media and religious identity: A case study of young witches. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 48(3), 501–514.

Google Scholar | Crossref | ISIOpenURL Tallinna Ulikool

Bittarello, M. B. (2008). Shifting realities? Changing concepts of religion and the body in popular culture and neo-Paganism. Journal of Contemporary Religion, 23(2), 215–232.

Google Scholar | CrossrefOpenURL Tallinna Ulikool

Campbell, H. A. (2013a). Community. In Campbell, H. A. (Ed.), Digital religion: Understanding religious practice in new media worlds (pp. 57–71). Routledge.

Google ScholarOpenURL Tallinna Ulikool

Campbell, H. A. (Ed.). (2013b). Digital religion: Understanding religious practice in new media worlds. Routledge.

Google ScholarOpenURL Tallinna Ulikool

Campbell, H. A. (2017). Surveying theoretical approaches within digital religion studies. New Media & Society, 19(1), 15–24.

Google Scholar | SAGE Journals | ISIOpenURL Tallinna Ulikool

Campbell, H. A., Evolvi, G. (2019). Contextualizing current digital religion research on emerging technologies. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 2, 5–17.

Google Scholar | CrossrefOpenURL Tallinna Ulikool

Campbell, H. A., Vitullo, A. (2016). Assessing changes in the study of religious communities in digital religion studies. Church, Communication and Culture, 1(1), 73–89.

Google Scholar | CrossrefOpenURL Tallinna Ulikool

Cheong, P. H. (2013). Authority. In Campbell, H. A. (Ed.), Digital religion: Understanding religious practice in new media worlds (pp. 72–87). Routledge.

Google ScholarOpenURL Tallinna Ulikool

Eisenlohr, P. (2017). Reconsidering mediatization of religion: Islamic televangelism in India. Media, Culture and Society, 39(6), 869–884.

Google Scholar | SAGE Journals | ISIOpenURL Tallinna Ulikool

Eurobarometer . (2005). Social values, science & technology [Report]. Special Eurobarometer225/Wave 63.1. https://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/archives/ebs/ebs_225_report_en.pdf

Google ScholarOpenURL Tallinna Ulikool

Evans, S. K., Pearce, K. E., Vitak, J., Treem, J. W. (2017). Explicating affordances: A conceptual framework for understanding affordances in communication research. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 22(1), 35–52.

Google Scholar | Crossref | ISIOpenURL Tallinna Ulikool

Faraj, S., Azad, B. (2012). The materiality of technology: An affordance perspective. In Leonardi, P. M., Nardi, B. A., Kallinikos, J. (Eds.), Materiality and organizing: Social interaction in a technological world (pp. 237–258). Oxford University Press.

Google Scholar | CrossrefOpenURL Tallinna Ulikool

Halpern, D., Gibbs, J. (2013). Social media as a catalyst for online deliberation? Exploring the affordances of Facebook and YouTube for political expression. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(3), 1159–1168.

Google Scholar | CrossrefOpenURL Tallinna Ulikool

Hamilton, M. (2000). An analysis of the festival for mind-body-spirit, London. In Sutcliffe, S., Bowman, M. (Eds.), Beyond New Age: Exploring alternative spirituality (pp. 188–200). Edinburgh University Press.

Google ScholarOpenURL Tallinna Ulikool

Hanegraaff, W. J. (1999). New Age spiritualities as secular religion: A historian’s perspective. Social Compass, 46(2), 145–160.

Google Scholar | SAGE Journals | ISIOpenURL Tallinna Ulikool

Hasebrink, U., Hepp, A. (2017). How to research cross-media practices? Investigating media repertoires and media ensembles. Convergence, 23(4), 362–377.

Google Scholar | SAGE Journals | ISIOpenURL Tallinna Ulikool

Hepp, A. (2014). Communicative figurations: Researching cultures of mediatization. In Kramp, A., Carpentier, N., Hepp, A., Trivundža, I. T., Nieminen, H., Kunelius, R., Kilborn, . . . R. (Eds.), Everyday media agency in Europe: The researching and teaching communication series (pp. 83–101). edition lumière.

Google ScholarOpenURL Tallinna Ulikool

Hepp, A., Hasebrink, U. (2018). Researching transforming communications in times of deep mediatization: A figurational approach. In Hepp, A., Breiter, A., Hasebrink, U. (Eds.), Communicative figurations: Transforming communications in times of deep mediatization (pp. 15–48). Palgrave Macmillan.

Google Scholar | CrossrefOpenURL Tallinna Ulikool

Hiiemäe, R. (2015). Maagiapärimusest Eestis: minevik ja tänapäev [Magic in Estonia: Past and Present]. In Petzoldt, L. (Ed.), Maagia. Tekkelugu, maailmapilt, uskumused, rituaalid [Magic. Origin, Worldview, Beliefs, Rituals] (pp. 153–178). EKM Teaduskirjastus.

Google ScholarOpenURL Tallinna Ulikool

Hjarvard, S. (2008). The mediatization of religion. A theory of the media as agents of social and cultural change. Northern Lights, 6, 9–26.

Google Scholar | CrossrefOpenURL Tallinna Ulikool

Hjarvard, S. (2013). The mediatization of culture and society. Routledge.

Google Scholar | CrossrefOpenURL Tallinna Ulikool

Hjarvard, S. (2016). Mediatization and the changing authority of religion. Media, Culture and Society, 38(1), 8–17.

Google Scholar | SAGE Journals | ISIOpenURL Tallinna Ulikool

Hutchings, T. (2013). Considering religious community through online churches. In Campbell, H. A. (Ed.), Digital religion: Understanding religious practice in new media worlds (pp. 164–172). Routledge.

Google ScholarOpenURL Tallinna Ulikool

Johns, M. D. (2015). Facebook gets religion: Fund-raising by religious organizations on social networks. In Brunn, S. D. (Ed.), The changing world religion map: Sacred places, identities, practices and politics (pp. 3781–3794). Springer.

Google Scholar | CrossrefOpenURL Tallinna Ulikool

Kantar Emor . (2017, March 3). Emor Passwordil: üle poole eestlastest usub kõrgemaid jõude ning ülivõimetega inimesi [Emor at Password: more than half of Estonians believe in higher powers and in persons with supernatural powers] [Blog post]. https://www.emor.ee/blogi/emor-passwordil-ule-poole-eestlastest-usub-korgemaid-joude-ning-ulivoimetega-inimesi/

Google ScholarOpenURL Tallinna Ulikool

Kluver, R., Cheong, P. H. (2007). Technological modernization, the Internet, and religion in Singapore. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 12(3), 1122–1142.

Google Scholar | CrossrefOpenURL Tallinna Ulikool

Kõiva, M. (2014). Äksi nõid—nõukogude aja selgeltnägija. [The Witch of Äksi – Clairvoyant Person and the Soviet Time]. Mäetagused, 58, 85–106.

Google Scholar | CrossrefOpenURL Tallinna Ulikool

Kõiva, M. (2015). Saatekirjaga rahvaarsti juures [The Doctor Sent Me to the Folk Healer]. Mäetagused, 62, 25–54.

Google Scholar | CrossrefOpenURL Tallinna Ulikool

Lauri, U. (2015, January 8). Maaleht püstitas tänase tiraažiga uue rekordi [Maaleht set a new record with today’s circulation]. Lääne Elu. https://online.le.ee/2015/01/08/maaleht-pustitas-tanase-tiraaziga-uue-rekordi/

Google ScholarOpenURL Tallinna Ulikool

Lohmeier, C., Böhling, R. (2018). Researching communicative figurations: Necessities and challenges for empirical research. In Hepp, A., Breiter, A., Hasebrink, U. (Eds.), Communicative figurations: Transforming communications in times of deep mediatization (pp. 343–362). Palgrave Macmillan.

Google Scholar | CrossrefOpenURL Tallinna Ulikool

Lundby, K. (2014). Mediatization of communication: Introduction. In Lundby, K. (Ed.), Mediatization of communication (1st ed., pp. 3–34). Gruyter de Mouton.

Google ScholarOpenURL Tallinna Ulikool

Markham, A. N. (2012). Fabrication as ethical practice: Qualitative inquiry in ambiguous internet contexts. Information, Communication and Society, 15(3), 334–353.

Google Scholar | Crossref | ISIOpenURL Tallinna Ulikool

Miczek, N. (2008). Online rituals in virtual worlds. Christian online service between dynamics and stability. Online: Heidelberg Journal of Religions on the Internet, 3(1), 144–173.

Google ScholarOpenURL Tallinna Ulikool

Possamai, A. (2005). In search of New Age spiritualities. Ashgate.

Google ScholarOpenURL Tallinna Ulikool

Rashi, T. (2013). The kosher cell phone in ultra-Orthodox society: A technological ghetto within the global village? In Campbell, H. A. (Ed.), Digital religion: Understanding religious practice in new media worlds (pp. 173–181). Routledge.

Google ScholarOpenURL Tallinna Ulikool

Ringvee, R. (2011). Riik ja religioon nõukogudejärgses Eestis 1991-2008 [State and religion in post-Soviet Estonia 1991-2008] [Doctoral dissertation, School of Theology and Religious Studies, University of Tartu]. https://dspace.ut.ee/handle/10062/17525

Google ScholarOpenURL Tallinna Ulikool

Rountree, K. (Ed.). (2017). Cosmopolitanism, nationalism, and modern paganism. Palgrave Macmillan.

Google Scholar | CrossrefOpenURL Tallinna Ulikool

Strmiska, M. (2005). Modern paganism in world cultures: Comparative perspectives. ABC-CLIO.

Google ScholarOpenURL Tallinna Ulikool

Tiidenberg, K. (2017). Ethics in digital research. In Flick, U. (Ed.), Handbook of qualitative data collection (pp. 466–481). SAGE.

Google ScholarOpenURL Tallinna Ulikool

Tiidenberg, K., Siibak, A. (2018). Affordances, affect and audiences—Making sense of networked publics, introduction to AoIR 2017 special issue on networked publics. Studies of Transition States and Societies, 10(2), 1–9.

Google ScholarOpenURL Tallinna Ulikool

Uibu, M. (2016). Religiosity as cultural toolbox: A study of Estonian new spirituality [Doctoral dissertation, School of Theology and Religious Studies, University of Tartu]. https://dspace.ut.ee/handle/10062/54063

Google ScholarOpenURL Tallinna Ulikool

Vahter, T. (2018, October 3). Esoteerika vabariik [Republic of esotericism]. ERR. https://kultuur.err.ee/866096/tauno-vahter-esoteerika-vabariik

Google ScholarOpenURL Tallinna Ulikool

Weber, M. (1978). Economy and society: An outline of interpretive sociology [TT—Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft. English]. University of California Press.

Google ScholarOpenURL Tallinna Ulikool

Author Biographies

Berit Renser (MA, University of Tallinn and University of Tartu) is a research assistant and a PhD student of Audiovisual Arts and Media Studies at the Baltic Film, Media, Arts and Communication School of the University of Tallinn, Estonia. Her current research interests include social media, belief systems, and health and wellbeing.

Katrin Tiidenberg, PhD, is an associate professor of Social Media and Visual Culture at the Baltic Film, Media, Arts and Communication School of Tallinn University, Estonia. She is the author of Selfies, why we love (and hate) them (2018), the forthcoming Sex and Social Media (2020, co-authored with Emily van der Nagel) and Metaphors of internet (2020, co-edited with Annette Markham). Tiidenberg is on the executive board of the Association of Internet Researcher and the Estonian Young Academy of Sciences. She is currently researching social media, participatory cultures, sexuality, and civic engagement. More info at: kkatot.tumblr.com